Tags

1960's, 76 trombones, band, being in love, broadway musical, buddy hackett, classic musical, eulalie shinn, gary indiana, golden age of musicals, good night my some one, good night my someone, goodnight ladies, goodnight my someone, harold hill, hermione gingold, Hollywood musical, if you don't mind my saying so, iowa, iowa stubborn, ireland, lida rose, marcellus, marcellus washburn, marching band, marian, marian paroo, marian the librarian, mayor shinn, meredith wilson, movie, movie review, mrs. shinn, musical, musical number, musical review, original, paul ford, pert kelton, pick a little, pick a little talk a little, prof. harold hill, robert preston, rock island, Romance, romantic cliche, romantic comedy, ron howard, sadder but wiser girl, seventy six trombones, seventy-six trambones, shirley jones, small town america, the buffalo bills, the music man, the sadder but wiser girl, til there was you, tommy jeelis, travelling salesman, travelling salesmen, trouble, trouble with a capital t, turn of the century, wells fargo wagon, winthrop, ya got trouble, you got trouble, zaneeta

“Please observe me if you will, I’m Professor Harold Hill,

And I’m here to organize the River City’s Boy’s Band!”

Let’s close out the summer with what I consider a must-watch summer musical. Doesn’t hurt that the main action kicks off on the Fourth of July.

“Missing another appropriate holiday-themed movie by several months. Ah, it’s good to be back.”

Based on the stories and childhood of Meredith Wilson, The Music Man weaves a tale of small town turn-of-the-century America, marching bands, charming charlatans, and the power of music that brings them all together. The original stage production notoriously beat West Side Story for Best Musical at the Tony Awards, though Tony and Maria got the last laugh when it came to the Oscars. I contend however that 1962’s The Music Man is a prime example of how to do a stage-to-screen adaptation. Through a combination of top-notch talent, music, staging, and witty witticisms it’s one of the crowning jewels of the Golden Age of Hollywood Musicals that lasted through the 60’s. Fifty years later its impact is still felt, at least musically. Chances are if you ambled down Main Street USA in any of the Disney parks you’ve heard the melodies of “Iowa Stubborn”, “Lida Rose”, “The Wells Fargo Wagon”, and “76 Trombones” playing in the background. It’s a staple for community theaters across the country. And like Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and The Sound of Music, it’s one of Seth MacFarlane’s most beloved and referenced musicals.

After a neat opening credits sequence comprised of stop-motion marching band dolls forming the shapes of musical instruments, we see a hapless traveling anvil salesman being chased out Brighton, Illinois by an angry mob. He escapes on a train headed to River City, Iowa and joins a car filled with other salesman. As the train chugs its way down the track, the salesmen grumble about modern inconveniences and the difficulties of their chosen work all in syncopated beat to the sounds of the engine.

Some years back I was fortunate enough to sit in on a Q&A of Stephen Sondheim centered around his latest autobiography, and when the interviewer congratulated him on being the first composer to incorporate rap into a musical (the rap in question being the Witch’s Rap from the prologue of Into The Woods), he corrected him. According to Sondheim, THIS sequence, “Rock Island”, was the first musical rap, and I can’t agree more. The cadence, the word sounds meticulously matching with the train’s noises, and the contempt and admiration the salesmen regard a certain figure throughout wouldn’t be out of place in a traditional rap. It says something when Hugh Jackman performed it as an actual rap at the Tonys with LL Cool J and T.I. and made it sound like the genuine article.

Conversation turns to one famous – or rather infamous – salesman who goes by the name of Professor Harold Hill. He’s referred to as a “music man” –

– because he sells instruments and uniforms for boys bands. But the salesman from earlier, Charlie Cowell (Harry Hickox), has got quite a few things to say about him. He reveals Harold is a con artist who convinces whatever unfortunate town he stops in to give him money for all the accoutrements of a marching band and promises to organize them with him as their leader, but skips out without teaching a note of music. The wave of anti-salesman mistrust he leaves in his wake is the reason why Charlie was given the bum rush. Charlie’s determined to catch up with him one of these days and give him his just desserts on behalf of all the honest salesmen whose careers he’s screwed over. But he knows there’s no way Harold would ever make his next mark in Iowa as the folk there are infamously stubborn and set in their ways.

Without warning a stranger in the corner who’s been silent throughout the proceedings gets up, announces that this talk of Iowa is intriguing and this is where he’ll get off. Before he disembarks Charlie mentions he never caught his name. The stranger replies, “I don’t believe I dropped it”, revealing it emblazoned on his suitcase.

Best. Introduction. Ever.

Robert Preston was a B-movie regular who occasionally did some stage work before landing the part of Harold Hill on Broadway, and not a day goes by that I don’t thank the theater gods for that because he is pitch perfect as the character. I have yet to see anyone who equals him in suave charm and quick wit (sorry Matthew Broderick, you tried). You’d think Hollywood would be clamoring to have Preston recreate his Tony-winning role on film, but Jack Warner, who was the head of Warner Brothers at the time, was dead-set on having an A-list Hollywood actor play the part. Jack really had a thing for celebrity casting in musicals regardless of their singing prowess (which would infamously bite him in the ass come the 1964 Oscars). He offered the part to Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, and Cary Grant, whom out of all the prospective choices gave Jack the best response: “I won’t even see the film if Robert Preston isn’t in it.” Reluctantly, Jack made an exception to his rule for Preston, and the rest is history.

Harold hops off before the train heads out, leaving behind a gaggle of awed salesman and a fuming Charlie. He makes his way into town and tries to introduce himself to the townsfolk but quickly learns that Charlie wasn’t kidding when he said Iowans are the most recalcitrant sonsabitches out there. The citizens sing of how proud they are of their inherent rudeness towards outsiders while following Harold in “Iowa Stubborn”, which I’m certain provided some inspiration for the musical number “Belle” from Beauty and the Beast.

“Look there he goes, he’s odd, no question, another salesman piece of swill. With his smile blinding white and his morals out of sight, what a puzzle to us all, that Harold Hill!”

After the “welcome” wagon disperses, Harold bumps into Marcellus Washburn (Buddy Hackett) an old friend and former partner-in-crime gone straight. He brings him in on his scheme for old times’ sake. Harold must create a need in River City for a boys band, preferably by following his time-honored tradition of painting something ordinary as unholy, corrupting and morally outrageous, getting the mindless masses riled up by playing on their own irrational fears of this foreign influence, and then selling his ridiculous solution as the only reasonable option to OH DEAR GOD NO.

“Go on, Shelf. Make the comparison. You KNOW you want to.”

ANYWAY, the only other thing standing in Harold’s way is the local librarian who gives piano lessons on the side and is musically intuitive enough to suss him out. But Harold’s got his own tried and true method of dealing with her. The solution to the first issue comes in the form of a new pool table delivered to the billiards hall and the sight of some scrappy young boys eagerly crowding outside the window for a look. Even though much of this musical is timeless – a little TOO timeless as of recent years, see above – it still makes me laugh seeing how the game of billiards and pool halls were seen as seen as outlandishly sinful back in the 1900’s. Over a hundred years later nobody bats an eye over it. Hell, when my family moved into our new house when I was six years old, the former owner left us her pool table and I’ve been handy with a pool cue ever since.

So the pool table is picked as the target of discrimination and the next thing you know Harold’s working his wiles on anyone who’ll listen. He quickly amasses a majority of the townsfolk who take to heart the warnings he espouses – today the children will be peeking into the pool hall, tomorrow they’ll be smoking, the day after they’ll be engaging with women of questionable repute in saloons and dancing the hootchie-cootch to ragtime music! Such horrors!

This number, “Ya Got Trouble”, is one of this musical’s cornerstones; the amount of parodies it continues to spawn decades later is a testament to that. Whether it’s a pair of huckster unicorns pawning off a magical cider-making machine, Conan O’Brien lamenting the state of 2000’s-era NBC, or most notably, the town of Springfield getting hyped over a monorail (which coincidentally was also penned by O’Brien), there’s at least one version out there that someone is familiar with regardless if they know its origins. It also showcases Robert Preston’s greatest strengths as Harold Hill. He’s not the strongest singer but the number calls for a rapid fire sense of timing and overwhelming force of presence, both of which he has in spades. Robert’s Harold sways the unwary townies through his sheer magnetism, plays on their foibles and fears like a fiddle, and leaves them – and us – wanting more, even after we see how unfounded the leaps of logic he presents are when we step back to dissect them.

“Hill 2020: Make River City Great Again…Again!”

The seeds of mob mentality planted, Harold pursues his next target, the librarian Marian Paroo (Shirley Jones) as she’s walking home. His attempts at an introduction fall flat, however, as she makes it clear she wants nothing to do with him. I know I made a reference to “Belle” with Harold’s arrival, but if there’s anyone worthy of a comparison to the titular heroine, it’s Marian. She’s witty and well-read, but trapped in a small and small-minded town who look down on her choices of literature as “dirty” and regard her as an outcast, naturally making her the source of plenty of unwanted gossip. Marian responds to this with a stiff upper lip and refusal to assimilate, but is secretly rather lonely. The only source of companionship is her sweet but meddling mother (Pert Kelton) who’s so Irish you’d think she came right off the set of Darby O’Gill, and her much younger brother Winthrop played by a very young Ron Howard.

Yes. THAT Ron Howard.

Marian gives a piano lesson to a young girl named Amaryllis while Mrs. Paroo unabashedly shares her opinions about why none of the women of River City take her seriously – namely she needs to find a good man to settle down with, stat. The two bicker the way only a mother and daughter can through the lesson, their arguments escalating with the music. Winthrop comes home and Amaryllis invites him to her birthday party. He initially refuses to answer since he has a very prominent lisp he’s embarrassed by. Amaryllis’ predictable guffaws over Winthrop’s response cause him to run up to his room in tears where he no doubt plans to expurgate Han Solo prequels as revenge. Amaryllis does feel remorse though since she’s hiding quite the precocious crush on Winthrop and takes his constant silence as a sign he doesn’t like her. Marian comforts her saying she can wish good night to “my someone” on the evening star until the right boy for her comes along. As Amaryllis plays her last practice piece for the evening, Marian sings the beautifully longing “Goodnight My Someone”. We also get the first instance of what I believe may have been a holdover from the original stage production. Following the end of a personal scene, instead of an iris out, everything goes completely black around the character in question leaving them standing out before it fades to the next scene. It doesn’t look exactly like a spotlight is shining on them, more like a tableau of sorts, and it’s utilized to great effect both comically or romantically depending on the scenario.

The next day, pompous spoonerism-prone Mayor Shinn (Paul Ford) and his wife (Hermione Gingold) lead the citizens in some patriotic Fourth of July activities, including a sing-along, some constantly interrupted attempts at reciting the Gettysburg Address, and a proud re-enactment of the Native Americans’ subjugation and denigration.

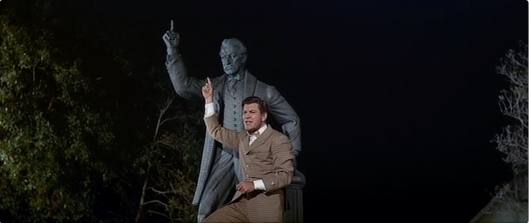

Mercifully this racist sham is halted by one Tommy Djilas, a brave and noble teenage soul and leader of the local gang of delinquents, who places a well-timed firecracker under Mrs. Shinn’s seat. Rather than be extolled for his act of human decency however, the crowd turns on Tommy and he’s apprehended by the sheriff. The argumentative school board can’t make up their minds on what act to present next and Harold takes the opportunity to raise some hell by bringing up the pool table again. As the assembly falls into chaos, Harold changes into his bandleader costume and takes the stage to announce his intentions of saving River City’s youth by starting up its first boy’s band. He captivates the throng with his accounts of the greatest marching bands he’s witnessed across America with “Seventy-Six Trombones”, another one of this musical’s high points. It’s catchy as all hell and Preston sells it yet again with his enthusiasm. While the lengthy choreographed crowd dance proceeding it doesn’t add much to the story, it’s still energetic and impressive to watch. It wasn’t until I watched the film again for this review that I noticed everyone involved is wearing red, white or blue or a combination thereof which amplifies the patriotic spirit pervading the scene.

Everyone marches out in their own fantasy version of a parade while Mayor Shinn and the school board look on proudly imagining their band as the pride of Iowa. Marian is the only one immune. After she bursts Shinn and the board members’ bubble with the simple question of “What band?”, Shinn is quick to recognize Harold’s got the town in his thrall and urges the board to get his references to see if he’s the real deal. Meanwhile, in an effort to get Mayor Shinn off both their backs, Harold rescues Tommy from the sheriff, recruits him as an assistant and to escort a pretty girl named Zaneeta home by way of the ice cream parlor, a surefire method to take the boy’s mind off any acts of vandalism. The sheriff congratulates Harold on his ingenuity but tells him he’s made two big mistakes:

- Mayor Shinn owns the pool hall and table that Harold’s been leading a tirade against.

- Zaneeta happens to be Shinn’s oldest daughter.

Harold causes an even bigger stir at the fireworks picnic that evening when the school board demands his credentials. Quick witted as always, he makes use of the members’ vastly differing vocal pitches as they argue among themselves and tricks them into forming a barbershop quartet. For the first time in years, the school board is in complete harmony (literally). Now anytime Harold has to keep them distracted, all he has to do is sing a snippet of a song and they’ll forget about everything to finish the rest.

“A running gag that serves an actual plot purpose. Even I can’t believe I pulled it off!”

This union further endears Harold in the citizens’ eyes, but Marian still refuses to see him as anything more than an obvious charlatan.

While posting flyers, Harold meets the clique of busybody housewives that make up the majority of Marian’s naysayers. Mrs. Shinn is their leader due to the fact that she has the biggest featheriest hat, and she alone shares her husband’s unsure thoughts on Harold’s intentions. But Harold turns her to his side by playing up her shifting her foot as a naturally graceful move worthy of Baryshnikov and offers her the position of head of the ladies’ dance committee he’s starting up concurrent with the band. Mrs. Shinn is instantly charmed over and agrees. Harold asks about inviting Marian to join but this sends the women into a loud gossiping frenzy. The movie doesn’t even try to make the comparison to a flock of cackling hens subtle.

Mrs. Shinn clarifies for Harold: not only does Marian snobbishly advocate books they consider too disgusting to be recycled into pulp (“Chaucer! “Rabelais!” “BAAAAL-ZAC!!”) but she made “brazen overtures” to wealthy and reclusive old miser Mr. Madison and was seen at his place quite frequently. When he died, he left River City the library, but left all the books to her, which I will never tire of using as a euphemism for being a sugar daddy.

The school board appears to hound Harold for his credentials again but he puts them off by tricking them into singing “Goodnight Ladies” against the ladies’ chorus. Fun fact: in preschool we sang this song at the end of the day whenever someone’s parents came to pick them up, which makes this of all things my introduction to The Music Man. Funny how life works like that sometimes.

As Harold and Marcellus hide out, they get to discussing their tastes in women. Marcellus has a nice thing going with one of the ladies in Mrs. Shinn’s circle but Harold’s got his eyes on “The Sadder But Wiser Girl” he believes Marian to be, the kind of girl who’s been there, done that, and got the hickeys to show for it. A decent number to be sure, and I really dig Seth MacFarlane’s cover, but it was Christi Esterle of Musical Hell who got me to view the song in a new light: in her video essay on “I Am/I Want” songs she stated that not all songs of that category have to be like “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” or “Somewhere That’s Green” or a fair bit of first-act Renaissance-era Disney songs. Case in point, this number. Harold submits to the audience that the kind of woman for him is not “an innocent Sunday school female”, yet that’s exactly the woman he’ll end up falling for by the story’s end. In this instance, the “I Want” song becomes an “I Think I Want” song, showing another step in the character’s eventual growth and turnaround from their initial ideals and wishes. Mind you, I’m not sure if they should be singing this in front of impressionable young Amaryllis, but the subtext flew over my head when I was her age and I’m hoping it does for her too.

Harold begins his courtship of Marian by harassing her at her workplace asking her for a date at the library, tempting her with images of sweet whispered nothings in the moonlight and rather descriptive longings for her in “Marian the Librarian”. I remember this being my favorite song from the movie when I was a kid and would watch on repeat for its playfulness and underlying romantic tug of war. Easily the best musical number to take place in a library outside of an episode of Arthur or Phineas And Ferb. The repeated shushings and “quiet please” signs quickly go ignored as Harold leads the teenagers there in rebellious percussive cavorting as he further attempts to grab Marian’s attention. Eventually Marian herself can’t help but get caught in the chaos, whipping off her glasses and literally letting her hair down as she’s swept into the dance. By the time Harold finally departs, she’s frustrated yet somewhat amused.

Harold continues to work his charms on the townsfolk, one of them being Mrs. Paroo, who signs up Winthrop to play the cornet without a second thought. Winthrop himself begins slowly opening up due to Harold’s influence as well. Harold further wins the Paroos over with an ode to his hometown Gary, Indiana. In the show it was an Act 2 solo for Winthrop but that was turned into a reprise and moved to here with a little soft-shoe routine in order to give Robert Preston more to do. Not that I’m complaining. It’s a catchy tune and he makes Gary sound like such a pleasant place to live. Surely if Harold must be honest about one thing, it’s that. Come on, gang, let’s all go to Gary, Indiana!

…never mind.

Marian isn’t thrilled seeing Harold getting along with her mother or Winthrop getting involved in the band. When Harold suggests Winthrop’s father veto, Marian coldly responds he’s been dead for some time and his untimely passing is one of the reasons why Winthrop is as withdrawn as he is. This naturally doesn’t do Harold any favors in regards to winning her over, but Mrs. Paroo, who’s been shipping Marian and Harold since the night he followed her home, assures him that she’ll come around.

Marian and Mrs. Paroo get to talking about what Marian’s looking for in a man and she waxes about it in “Being in Love”, which was written for the movie and replaced “My White Knight”. Honestly, it’s the one song I don’t like. It stops the film so Marian can list all the different men she’s had crushes on and the desired qualities of her dream boy. Musically it wanders all over the place, jazzy one moment and operatic and slow the next. I like the tune of what I think is supposed the main melody and it is used effectively as Marian’s leitmotif throughout the movie, but the lyrics do nothing for me. Skip it and you miss nothing.

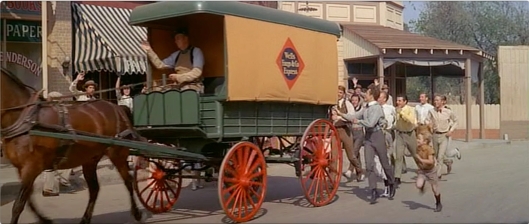

At the library Marian finds a book about Indiana’s educational institutions which has the evidence she needs to discredit Harold. But as she takes it to Mayor Shinn, he and the rest of River City are overcome by the arrival of the Wells Fargo Wagon carrying the band instruments into town.

“We’re also giving out plenty of interest-riddled bank accounts under all your names, whether you need them or not!”

“The Wells Fargo Wagon” is one of The Music Man’s signature tunes. I want to like this whole number, I really do, but the film’s rendition is pretty sloppy in its first half. It starts with two little girls being the first witnesses to the wagon’s arrival, but when they open their mouths to sing the voices that come out belong to someone obviously twice their age. The soloists that vocalize their praises of the wagon’s past deliveries before the chorus kicks in along with those inane merry-go-round whistles are also grating. Still, it’s not without plot significance. Winthrop gets so excited that he breaks into his own solo and regales Marian with how beautiful his own cornet is, the most he’s spoken at once in an age. Seeing the townsfolk united by the thrill of the band coming together, her brother happy for the first time in years and that Harold came through on some of his promise, Marian tears out the incriminating page from her book before handing it over to Mayor Shinn.

A date is set for the town social where the band is set to premiere and practice is quickly underway for both them and Mrs. Shinn’s dance committee. Harold naturally BS-es his way through teaching the children with his “revolutionary” method which he calls the think system – just play the notes in your head and it’ll come out naturally regardless of practice, proper instrument handling, or talent.

“One could argue it’s still being used today by half the people on the radio.”

Progress is also made with Harold and Marian’s and Tommy and Zaneeta’s relationships. When Mayor Shinn loudly confronts Tommy at the ice cream parlor for seducing his girl, both they and Mrs. Shinn stand up to him; a far cry from the submissive ladies they were before Harold came along. Blustered and humiliated, Mayor Shinn warns Tommy and Harold he’s keeping an eye on them both and sarcastically thanks Marian for wasting his time with her book. Marian commends Harold for giving Tommy the benefit of the doubt and begins to accept Harold’s compliments to her. After some talk about the unusual progressive method Harold is teaching, she gives him permission to court her the night of the social.

As the big event rolls around, Harold comes within inches of being accosted by the school board but he puts them off with, what else, a sing-along. This time it’s a fine rendition of “Lida Rose” which becomes another counterpoint duet with Marian as she ponders her feelings for Harold in “Will I Ever Tell You”. It’s also the one time in the movie that’s framed the most like a theatrical production. I can imagine stagehands moving around sets and props in the black area between the two spotlights.

Winthrop returns from practice in a pleasant talkative mood thanks to some off-screen surrogate-father-son bonding with Harold and shares his take on the aforementioned “Gary, Indiana” reprise. If you’re drinking while watching this movie, don’t take a shot every time Mrs. Paroo winces as Winthrop spits in her face. You might not make it through to the end.

Mrs. Paroo takes Winthrop go get ready for the social leaving Marian to wait for Harold. And who should come thumping down the street but the salesman from before, Charlie Cowell, with a fistful of damning evidence against Harold. His train’s making a brief stop in River City and he’s taking advantage of it by personally delivering the papers to Mayor Shinn. At first Charlie hopes to get Marian on his side seeing how she’s musically inclined enough to see through Harold from the beginning, but when she inadvertently reveals Harold’s already won her over he won’t trust Marian to leave her with the evidence, even though he rather awkwardly keeps hitting on her.

See, Charlie and his crusade against Harold is a prime example of something I like to call the William Atherton Principle: no matter how right someone is, their words of caution will be ignored in proportion to how much of an asshole that someone is. William Atherton as Walter Peck in Ghostbusters is one of the biggest dicks in cinema, though he has a point. The Ghostbusters ARE wielding dangerous untested technology that poses a hazard to anyone living or dead. But because he’s such a prick to anyone he meets and endangers the Ghostbusters, New York City, and the world as we know it to prove his point, we’re loathe to side with him. And the same goes for Charlie. Morally he’s is 100% in the right for trying to bring Harold to justice; Harold’s conned who knows how many innocent people out of money, seduced just as many women to keep them quiet, and ruined the prospects of other traveling salesmen trying to make an honest living. But doing so would undo all the good Harold’s brought to River City. Plus Charlie is acting like a total creep towards Marian with his “nice guy” act, so who’s to say he’s not above what Harold’s done to other women?

Marian encourages Charlie’s flirting long enough to make him choose between meeting Mayor Shinn or chasing after his train. Charlie storms off but not before declaring to Marian that Harold’s got a girl fooled in every state and she’s slated to be just another conquest. Also she’s, like, a total slut who’s like a three out of ten, and it has nothing to do with the fact that she turned him down, for real. This give Marian something to pause over – not the slut thing, she already gets that everyday from the gossiping biddies. Now that she’s finally feeling something for Harold, the thought that she might be nothing to him after all is enough to almost break her heart.

Harold arrives but Marian has too much on her mind to think of canoodling on the front porch. Under the guise of learning more about the think system she tries to gage whether he’s gotten around as much as Charlie said. It’s a great conversation they have; they’re talking about the same thing yet they’re both on completely different levels. It’s only when Marian mentions how one hears rumors about traveling salesmen that Harold begins to catch on. In turn he brings up the rumor he may or may not have heard about her which leads Marian to open up about “Uncle Maddy” – see, the miser Madison that half the town believed Marian to be involved with was in actuality a close friend of the Paroos, and when he died he left Marian the library position so she could support her family. Harold gets her to realize that the same narrow-minded jealousy that started those rumors about her could easily apply to salesmen, leaving Marian to reason to herself out loud that Charlie’s claims must have been born from that jealousy. Harold is clearly still confused but rolls with it as he always does. With both misunderstandings cleared up, he asks Marian to rendezvous with him at the footbridge in the park, which has a certain reputation surrounding it.

“Ah, the footbridge. Good times, good times.”

The social kicks off as Marcellus leads the teenagers in a wild new song and dance called the Shipoopi. And before you ask, yes, this is where Family Guy got it from.

Once it wraps up and the ladies dance committee get their graciously not-racist artistic depictions of Grecian urns underway, Harold strolls past teams of unrepressed and unrepentant teenagers doing their teenage thing down to the footbridge. It’s there we get a beautiful understated – and in the case of this movie, underrated – scene of Harold alone with his thoughts. While waiting for Marian, he gazes into the water. The image of a well-dressed marching band appears, their instruments at the ready. All they’re waiting for is their leader.

Harold takes a stick, raps on the railing for attention, and begins to conduct. He guides passionately like Leopold Stokowski, his eyes shut in ecstasy as a soulful rendition of “Goodnight My Someone” wells up from the vision.

But partway through, he stops.

Earlier, Marcellus compared Harold’s show at the gymnasium to a famous bandleader he liked to imitate. Harold showed off a bit of that flair for him before stopping himself, waving it off as “kid’s stuff”. Alone, however, he cannot deny his one wish – for his role of a great bandleader to be genuine. Yet as much as he secretly dreams it, he knows it’s nothing but a fantasy. That band he sees before him is as real as his own musical skills. Why try to change what can never be? Harold snaps the twig in two and tosses it in the river. The ripples shatter the illusion, and the music dies with it.

Marian finally arrives. She confesses that she almost didn’t come at all but she needed to tell Harold just how much she has done for her since the day he came, which she does in the eleven o’clock number “Til There Was You”. You might be more familiar with the Beatles’ cover or even the version sung by the little old lady in The Wedding Singer, but this is where it originated from and I still vouch that this is the best version. Shirley Jones’ voice is sweeping and operatic, much more suited for this ballad than “Being in Love”, but she never goes over the top and the song doesn’t stray into cloying territory, not once. It’s genuinely romantic and even brings a tear to my eye.

Marcellus briefly draws away Harold to inform him the money’s collected, the train out of town is waiting and the sooner he amscrays the better, but Harold’s not going anywhere until he finishes his business with Marian. On returning Marian admits she knew his game right from the start and confirmed it in her research – Harold claimed he graduated from The Gary Conservatory Class of ’05, but there was no Gary Conservatory in ’05 because the town wasn’t even built until ’06! She gifts him the page with that information, and that’s when Harold starts to realize that his act of being head over heels for Marian may not have been an act after all…

But things take a turn for the worse when Charlie and Mayor Shinn interrupt the ladies’ concert and expose Harold, and faster than you can say “kill the beast” the town forms a torch-wielding angry mob to track him down. Marcellus does his best to distract anyone he meets while Mrs. Paroo searches for a heartbroken runaway Winthrop. Harold, meanwhile, has been walking Marian home so she can powder her nose. As he waits outside he sings a little bit of “76 Trombones” to himself while she replies from her room with verses of “Goodnight My Someone” until halfway through they switch songs. I wasn’t musically inclined enough to notice myself but on doing my research I found ingenious subtle proof that this scene reveals how Marian and Harold were destined to be together from the beginning – “Goodnight My Someone” and “76 Trombones” are the same exact song, only played at different tempos. Their reversal to the other’s tune shows how much of an effect they’ve had on each other.

Marcellus and Mrs. Paroo let Harold know the jig is up and Marian assures him she’ll be all right as long as he escapes before the mob catches up. Yet for the first time in his career, Harold is torn between leaving and staying. Winthrop bumps into Harold and tearfully takes his anger out on him. I love Robert Preston’s acting in this moment. For the first time he comprehends that he hasn’t only screwed over the adults in the past but the children whose hopes for a band he’s gotten up. How many Winthrops has he won over only to dash their dreams? In this scene he’s forced to look directly at the result of his lies, and for that split-second you see that horrific realization flash across his face.

“What have I done, sweet Jesus what have I done, become a thief in the night, become a dog on the run!”

There’s another line here that I think is equally important and ties back to the scene of Harold at the bridge. Harold admits he think Winthrop is a genuinely good kid and wanted him to be a part of the band so he wouldn’t be moping about by his lonesome all the time. Winthrop asks “What band?” in the same way Marian did before and after a moment’s pause, Harold replies “I always think there’s a band, kid.” To Harold, somewhere out there, there’s another town always waiting for him, another band waiting to be form, another show to put on and dream to pretend to make come true. He may be doing it for the money, but I like to believe there’s a part of him that’s bought what he’s been selling all these years, and it’s what drives him to keep his schemes going as well as the allure of cash.

Marian tells Winthrop she’s glad that Harold came to River City after all is said and done. All the fanfare and fireworks he promised came to be through the impact he made on the town, and how everyone changed for the better because of him, which is why she never ratted him out. This is what cements Harold’s decision to stay. He openly admits he loves Marian with a tearjerking short reprise of “Til There Was You” moments before the mob carts him away to face the music.

A makeshift trial is held at the school with Mayor Shinn serving as judge, jury and executioner. He’s already prepared to give Harold the tarring and feathering of a lifetime, as are a good many of the River City citizens. Marian makes a heartfelt appeal to them by reminding them of how miserable life was before Harold came. Everyone, Mrs. Paroo, Mrs. Shinn, the ladies’ dance committee, the school board, Tommy and Zaneeta, all the mothers and fathers and townsfolk that once took smug delight in their hostility towards others, stands up in defense of Harold –

“I’m Harold Hill!” “I’m Harold Hill!” “I’m Harold Hill, and so is my wife!”

– that is until Shin reminds everyone that Harold still took their money with nothing to show for it. It looks like its curtains for him but the band shows up in their shabby uniforms ready to play for a captive audience. Encouraged by Marian, Harold takes the stand with a broken yardstick in place of a baton, tells his boys to think like their lives depend on it, and…

Actually, it goes over SLIGHTLY better than that. It’s still bad, but the parents in the audience are so overcome with pride in seeing their children playing that to them it’s the sweetest music in the world. And that’s what saves Harold. No joke, I think this ending is perfect. It’s a great punchline and feels like a natural outcome to everything that happened before. The only way this would have felt like a copout would be if the band did inexplicably sound perfect at the moment of truth.

Everyone exits the school as the sun rises on a new day, and something incredible happens. As the band marches out, their uniforms become shiny and new in the eyes of the onlookers. The marchers, baton twirlers and players, now multiplied ten times over complete with – you guessed it – seventy-six trombones, file out down Main Street past cheering crowds and a very bewildered Charlie, filling the air with music. In reality it may be a simple, inexperienced boy’s band, but seen through the eyes of the citizens of River City, it’s something grand to be proud of. And conducting them in their march enthusiastically waving in time to the music is their leader, Professor Harold Hill.

The dream is real at last.

This adaptation captures all the charm and originality of the Broadway show. It’s on my top 10 list of favorite musicals for a very good reason. The songs are unforgettable, the characters are lovable with their own quirks and hidden depths, and the performances are excellent. The employment of noted character actors from the day in place of stars allows the film to not be overshadowed by the presence of standout faces and lets the actors make the parts their own. Paul Ford’s Mayor Shinn is a standout; he truly has a grasp of the English language unto his own (“You watch your phraseology!”) The way River City looks encapsulates the innocence and optimism of the era with its white picket fences and Independence Day regalia. And yes, I make it a point to watch it every Fourth of July weekend if just for that. This was one of the movies I got hooked on thanks to my grandmother, and when I went to her house after school every day I had to put it on at least once. To this day I can recall most of the lyrics from any given song from memory. By all means, seek it out and let the music carry you away.

Thank you for reading. If you like what you see and want more reviews, vote for what movie you want me to look at next by leaving it in the comments or emailing me at upontheshelfshow@gmail.com. Remember, you can only vote once a month. The list of movies available to vote for are under “What’s On the Shelf”.

If you want to support me and donate to WordPress’ one and only totally not fake boy’s band, please consider supporting my Patreon. It’s completely optional, you can back out any time you choose, and it comes with perks like extra votes and adding movies of your choice for future reviews. Special thanks to Amelia Jones and Gordhan Ranaj for their contributions, AND for donating to this month’s Charity Vote Bonuses. I’d also like to thank Abigail Kane for her $20 charity donation as well. In keeping with the bonuses promised, John Carpenter’s brilliant and bonechilling 1982 remake of The Thing has been added to The Shelf, and you can expect your requested review of Disney’s Pinocchio in a few months!

Artwork by Charles Moss.

Great review! I especially loved seeing what Gary, Indiana actually looks like and the crossed-out “harrassed at the library”, lol!

I also didn’t realize the Belle and Iowa Strong similarities before.

I haven’t seen this film adaptation in a while, but I definitely love the songs!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another great review, Shelf! In fact, it may be one of your best yet! I liked how you went into Harold Hill’s character arc, as well as the introduction of the William Atherton Principle. See you next month. In the meantime, I’ll be working on my own essays.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Good luck with your essays!

LikeLike

Another wonderful review of a fantastic movie, that I’ve been introduced to thanks to you. Seriously, without these reviews, I doubt I’d ever consider checking out, some of these movies. And I’m very thankful for that. Keep it up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Happy 2020! / Blog Plans for the Year / Poorly Explained Movie Plots | Up On The Shelf

Actually, the musical was released the same year as Kurosawa’s ‘The Lower Depths’, which also incorporated proto-rapping.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Christmas Shelf Reviews: Klaus (2019) | Up On The Shelf